Reflexive and participatory mode documentary are both auteurially involved ways to make a documentary. Every documentary needs an auteur, but these are the few that actually oblige the maker to look back at themselves in some way. The way in which they look back at themselves varies enough to divide their mode.

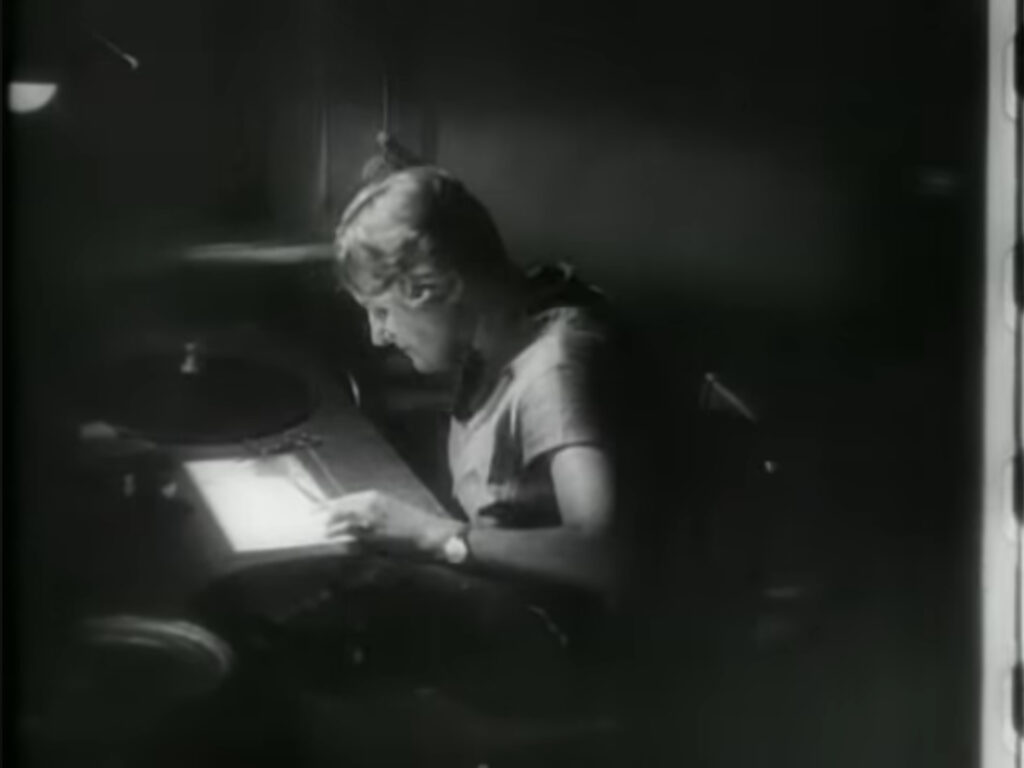

In order to make a reflexive documentary, the maker must first find something to comment on about documentary itself. A blatant example of this is Man with a Movie Camera (1929) by Dziga Vertov. It is not the film in its entirety that reflects on the making of documentary, but a specific segment about part way through. This is where we watch the editor, Yelizaveta Svilova, editing clips of the documentary together. We see these clips inter-spliced with the documentary itself, making the audience consider the work behind the scenes. Any moment we see the man with the movie camera, the makers are reflecting on the medium itself. The playful superimposition makes the camera operator seem larger than life but also smaller than a glass of alcohol. These moments lack realist representation, but this “sense of formal abstraction” as put by Nichols, is what puts the viewer into the context. The moment we are watching the editor make the film we are watching; the audience is let into the continuity manipulation at play.

Participatory mode finds itself less tool centric and more auteur centric. An example of this is Shermans March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation (1986) by Ross McElwee exemplifies this auteurial focus. This is a personal work, almost like a diary entry or a day in the life of the man filming it. It exemplifies the mode by being very personal, watching personal interactions; in this case, those of Ross and the women he finds himself entangled with over the span of his time following the path of William Sherman. It became a personal diary where Ross expressed his fears of nuclear war and his opinions of the women he interacted with and periodically fell in love with. The picture is often of conversation with women, finding great importance in synced sound through the film. Periodically there is narration as a tool to give us insight into the filmmaker. He is a social actor in the film just as any of the women are.

There are defining factors to each mode, but where do they overlap? Well, they overlap by being commentary. One is commentary on the medium, focusing on the interaction between audience and auteur, whilst the other is commentary on the situation through interaction between the auteur and the interlocutors. They also share similar ethical difficulties. Both of them are projections of the auteur in some way, which is cause for bias and possible goading or misrepresentation. People are being placed into a commentary heavy context and are subject to the warping of the auteur’s lens for better or worse.

These modes are very different, but this profound difference from the other modes, often playing in opposition to them, is what makes them so similar. The author has something to say and they are going to say it through their lens and acknowledge their tools wither overtly or inadvertently. The auteur is always looking at that camera lens—metaphorically speaking—it’s a question of whether they’re looking at the glass or staring at their own reflection.